Depreciation

When a non-current asset is bought by a company for use in the operations of a business it must be depreciated over a number of years to reflect the “using up” or consumption of the asset. Take for example a business buys a computer to be used in the day-to-day operations of the business. This asset will have a useful life of only about 3 or 4 years by the end of which it will become obsolete as more powerful computers will be available to replace it at roughly the same price.

What is Depreciation?

Depreciation is an expense that reflects the diminution in value of an asset that is used in a business over a number of years.

There are many causes of depreciation the following are the main reasons:

Wear and Tear

Regular use and physical deterioration reduce the value of tangible assets like machinery, vehicles, and equipment over time.

Obsolescence

Technological advancements, regulatory changes, or shifts in consumer preferences make assets outdated or less useful.

Depletion

The reduction in value of natural resources (e.g., mines, oil reserves) due to extraction or harvesting.

Time and Aging

Assets lose value simply by aging, regardless of their usage, such as software licenses, patents, or buildings.

External Factors

Economic conditions, environmental forces, poor maintenance, or changes in market perceptions can accelerate depreciation.

- Take, for example , a computer. It will last for several years and be used consistently over that time. In everyday terms, people often assume the "cost" of an asset like a computer occurs when the cash is spent. However, in accounting, this is not the case. When a business pays cash for a computer, it represents a reorganisation of the balance sheet: the cash asset decreases while the equipment asset increases. Depreciation is the method used to recognise the asset (the computer) as an expense over time. In other words, it reflects how the computer is "consumed" or "used up" during its useful economic life.

- In accounting, it is necessary to make several assumptions about a non-current asset before it is depreciated. First, you must estimate its useful economic life. The "useful economic life" differs from its actual life, which may be significantly longer. For example, a computer could potentially last 15 years if well-maintained, but this is unlikely to happen, as newer, more powerful computers are introduced long before then, capable of running more effective software. If your business does not adopt these updated computers and software, it would be at a significant disadvantage compared to your competitors

- The next assumption you need to make about your asset is its "residual value" or "salvage value." This refers to the expected amount the asset will be worth at the end of its useful economic life. Take, for example, a vehicle used in the operation of a business. It will always have a scrap value, as the materials of the vehicle can be reused and recycled, giving them at least a material value.

- The next phase is to then calculate the depreciable amount which is the cost of the asset minus its salvage value. The result of this calculation is the depreciable amount which must be expensed in the form of a depreciation expense over the useful economic life of the asset.

As the non-current asset is depreciated there are a number of accounts that interact with each other to systematically manage the depreciation of the asset, they are the following

- Asset Cost Account - this is the real account that represents the initial cost of the asset

- Accumulated Depreciation Account - this is the contra asset account that is associated with the assets cost account. This account has a normal credit balance and the netting of the accumulated depreciation account (credit balance) with its corresponding asset cost account (debit balance) gives what's known as the “Net Book Value” of the asset.

- Depreciation Expense Account - This is the temporary or nominal account that represents the diminution in the value of an asset over a set period of time (usually one year)

This best way to show the student how these accounts interreact would be to take an example of a vehicle being bought and used in a business. Let’s for example say our business is a bus company that transports members of the public around a city for fares. When we purchase a new bus, we don’t intend to resell it for a profit, we intend to use the vehicle in the operation of our business transporting people. The asset is therefore a non-current asset and not a piece of stock for resale.

In our example

our bus is purchased (2024-01-01) for EUR 110,000 and has a useful economic life of 5 years, its salvage value is EUR 10,000. We have decided to deprecate this in a straight-line fashion (more on depreciation methods later) over a period of 5 years with equal instalments of EUR 20,000.

The following are the journal and adjustment entries to reflect the purchase and depreciation of the asset for the first year of operations.

This Journal entry represents the day the day the new bus was purchased. Another way to describe the date of purchase is the date the business took physical possession of the new bus.

| Date | Jn No | Details | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024-01-01 | 1 | Non-current Asset (Bus) | 110,000 Dr | |

| 2024-01-01 | 1 | Bank | 110,000 Cr |

This journal entry would be an adjusting entry at the end of the fiscal year and it represents the recognition of the depreciation expense that has been incurred on the bus for the year. You see the contra asset account (accumulated depreciation) has been credited and the expense has been debited. The “Net Book Value” is the sum of the asset cost and the accumulated depreciation account.

| Date | Jn No | Details | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024-12-31 | 2 | Depreciation Expense | 20,000 Dr | |

| 2024-12-31 | 2 | Accumulated Depreciation | 20,000 Cr |

This journal entry represents the “closing off” of the nominal or temporary account at the yearend to the profit and loss account. This process is followed with every nominal account and depreciation expense is no exception

| Date | Jn No | Details | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024-01-01 | 3 | Income st./P&L Acc. | 20,000 Dr | |

| 2024-01-01 | 3 | Depreciation Expense | 20,000 Cr |

This adjustment process would continue in the same way each year of operations until the asset is fully depreciated, in practical terms this would mean that accumulated depreciation contra account would have a credit balance equal in number to the cost less the salvage value of the asset.

| Year | Cost | Dep. Exp. | Acc. Dep. | Book Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 110,000 Dr | 20,000 Dr | 20,000 Cr | 90,000 Dr |

| 2025 | 110,000 Dr | 20,000 Dr | 40,000 Cr | 70,000 Dr |

| 2026 | 110,000 Dr | 20,000 Dr | 60,000 Cr | 50,000 Dr |

| 2027 | 110,000 Dr | 20,000 Dr | 80,000 Cr | 30,000 Dr |

| 2028 | 110,000 Dr | 20,000 Dr | 100,000 Cr | 10,000 Dr |

The Methods of Depreciation

There are two main methods of depreciation and a few lesser used methods of depreciation.

The two main ones are called the Straight-Line Depreciation and Reducing Balance Depreciation.

Straight-Line Depreciation

Straight-Line Depreciation is the most commonly used and simple methods of depreciation. It is simply the cost of the asset less its residual value depreciated in equal parts over the useful life of the asset. The example of the Bus depreciating above is an example of straight-line deprecation. The bus had a depreciable value of EUR 100,000 and was deprecated of a time period of 5 years in equal parts of EUR 20,000 per year. The majority of non-current assets that are deprecated in this way which is good as it is the simplest and straight forward.

Reducing balance deprecation

Reducing balance depreciation is a method of depreciation that uses the changing book value of the non-current asset as a determining factor in the calculation of the following periods depreciation expense amount. This means that the net of the figure of the assets cost and accumulated depreciation forms the value by which the percentage depreciation charge is calculated from and inputted into the general ledger.

A key feature of Reducing balance deprecation

is that the depreciation expense in the income statement is higher in the earlier years and gradually decreases over time, without ever fully depreciating the asset to its residual value. A business might choose the reducing balance method because it estimates greater benefits from the asset’s use in the early years, aligning with the matching/accrual principle in accounting. Additionally, the asset may incur lower maintenance costs in its early years, whereas later years often require higher expenses to maintain its operational capabilities. A good example of this is the case of buses: newer vehicles typically require less maintenance than older ones, a fact that is almost universally true.

Less redo our bus example except this time with a 25% reducing balance method of deprecation. We estimate that this will better reflect the economic life of the bus.

| Year | Cost | Dep. Exp. | Acc. Dep. | Book Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 110,000 Dr | 25,000 Dr | 25,000 Cr | 85,000 Dr |

| 2025 | 110,000 Dr | 21,250 Dr | 46,250 Cr | 63,750 Dr |

| 2026 | 110,000 Dr | 15,938 Dr | 62,188 Cr | 47,813 Dr |

| 2027 | 110,000 Dr | 11,953 Dr | 74,141 Cr | 35,859 Dr |

| 2028 | 110,000 Dr | 8,965 Dr | 83,105 Cr | 26,895 Dr |

As demonstrated, the depreciation expense is higher than the straight-line 20% example during the first two years, but it drops below EUR 20,000 per year thereafter. This method likely provides a more accurate reflection of the bus’s useful economic life, as the later years typically involve significantly higher maintenance expenses compared to the first two years.

More depreciation methods

We will now cover additional depreciation methods that are less commonly used.

1. Units of production / Units of Activity Method

The Units of Production method varies the depreciation expense on the basis of the use of the asset. This is a much more precise method of depreciation as it varies the expense on level of use of the asset not the passage of time.

For example, in a highly regulated industry such as commercial aircraft transportation, depreciation calculations are often based on the number of hours an aircraft has flown. Due to the demanding engineering and safety standards, the aircraft manufacturer can estimate with a high degree of accuracy the total number of usable hours for the aircraft. Consequently, depreciation for these assets is calculated based on usage (hours flown) rather than the passage of time.

| Cost of Aircraft | Estimated Residual Value | Depreciable Amount | Hours Used Total | Depreciation per hour |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EUR 50,000,000 | EUR 3,000,000 | EUR 47,000,000 | 10,000 Hours | EUR 4,700 |

In this example, depreciation is calculated by multiplying the hours used each year by the depreciation rate per hour. This approach results in a variable depreciation expense each year, reflecting the actual physical usage of the non-current asset rather than adhering to a fixed mathematical formula.

| Year | Hours Flown | Depreciation Expense |

|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 1500 | 7,050,000 |

| 2025 | 2500 | 11,750,000 |

| 2026 | 2300 | 10,810,000 |

This approach can also apply to other assets, such as an oil well or a goldmine, where precise estimates are made regarding the total amount of material that can be extracted from the ground. The measurement of the material extracted each year can then be used to calculate the annual depreciation charge, ensuring it aligns closely with the asset’s actual usage.

2. Sum of the years’ digits depreciation

This method is similar to the reducing balance method in that it places a higher depreciation charge in the early years and the charge become progressively less as the asset approaches the end of its life. The following example will explain the method.

A business purchases a machine for use in its manufacturing process on 2024-01-01 for EUR 10,000. The machine has a useful economic life of five years. Using this method of depreciation calculation, we sum the digits of the years in the asset's economic life. In this case, the calculation would be as follows:

1+2+3+4+5 = 15

In the first year we calculate the depreciation as 5/15 multiplied by EUR 10,000 = EUR 3,333.33, the second year 4/15 multiplied by EUR 10,000 = 2,666.67 and so on.

| Year | Calculation | Depreciation Expense |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5/15 x 10,000 | 3,333.33 |

| 2 | 4/15 x 10,000 | 2,666.67 |

| 3 | 3/15 x 10,000 | 2,000.00 |

| 4 | 2/15 x 10,000 | 1,333.33 |

| 5 | 1/15 x 10,000 | 666.67 |

| Total | 10,000.00 |

Disposing of a non-current asset

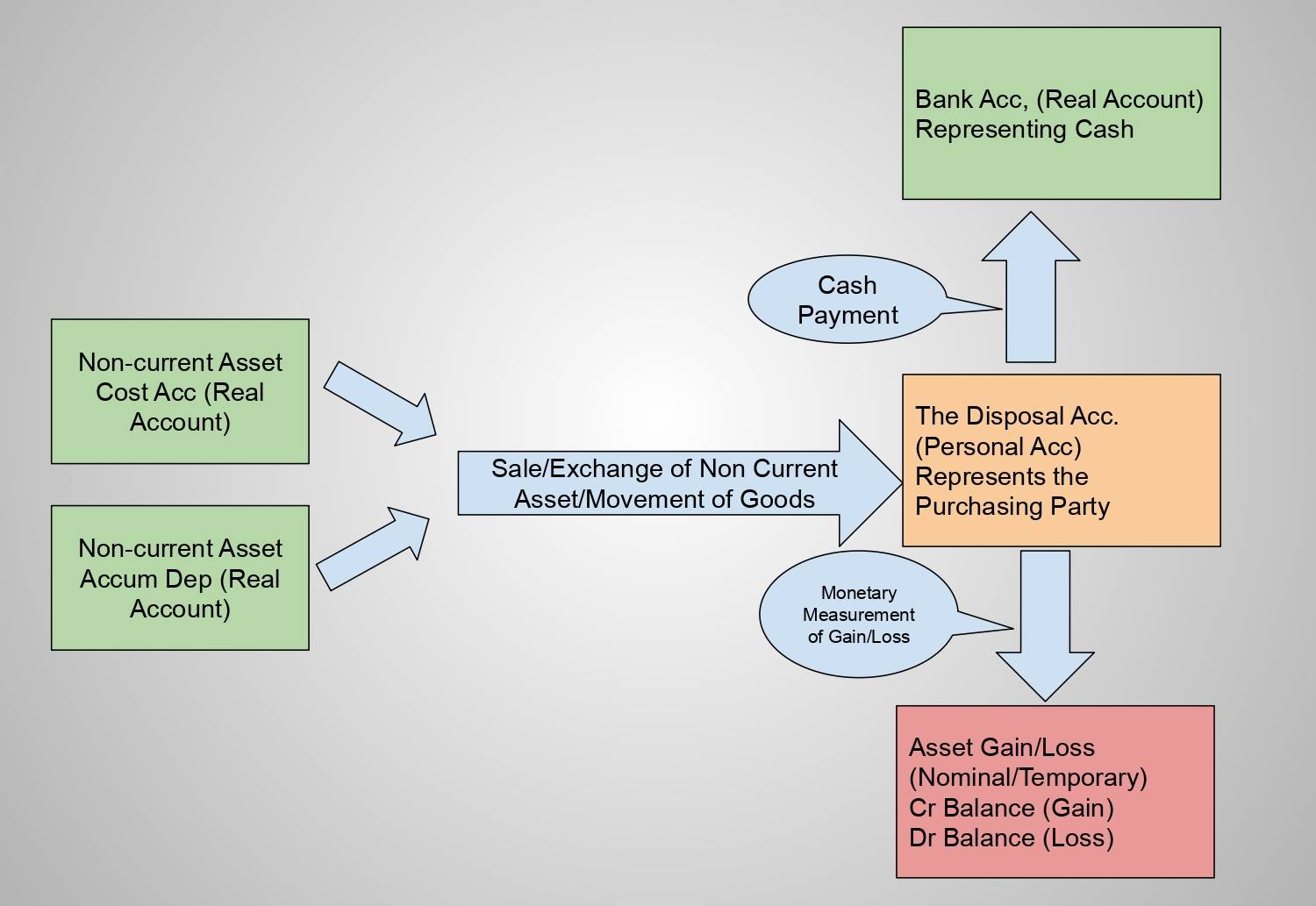

Disposal of a non-current asset before the end of its useful economic life (or even after) results in the use of the disposal account. The disposal account represents the party that is buying the company’s non-current asset.

Depreciation is not a method for estimating an asset’s market value; rather, it is a logical and systematic approach to allocating the asset’s cost over its useful economic life. Consequently, a non-current asset may be sold for more or less than its book value. When an asset is sold, its cost and accumulated depreciation are transferred to the disposal account to represent the net book value of the asset. The cash received for the asset is credited to the disposal account and debited to the bank account, reflecting the payment made by the buyer. Any remaining balance in the disposal account (which is common) must be either debited or credited to the Income Statement (Profit and Loss account), as no amount can remain outstanding to either the purchaser or the seller once the transaction is completed.

By way of an example lets go back to the purchase of the new bus, let’s say we were using straight line depreciation and we sold the asset at the end of 2026 for EUR 70,000. The following are the journal entries that we must use to reflect this transaction

This journal represents the sale of the bus (physical removal) to the third party (disposal account)

| Date | Jn No | Details | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2026-12-31 | 5 | Bus Disposal Account | 110,000 Dr | |

| 2026-12-31 | 5 | Bus Cost Account | 110,000 Cr |

This journal entry represents the removal of the accumulated depreciation which must be reflected in the disposal account as it is necessary to reflect the net book value of the bus

| Date | Jn No | Details | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2026-12-31 | 6 | Bus Accumulated Depreciation | 60,000 Dr | |

| 2026-12-31 | 6 | Bus Disposal Account | 60,000 Cr |

This journal entry reflects the cash payment from the purchaser to the seller (the business) of the asset (Bus)

| Date | Jn No | Details | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2026-12-31 | 7 | Bank | 70,000 Dr | |

| 2026-12-31 | 7 | Disposal Account | 70,000 Cr |

This represents the gain on disposal, that is the difference between the cash received and the net book value.

| Date | Jn No | Details | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2026-12-31 | 8 | Disposal Account | 20,000 Dr | |

| 2026-12-31 | 8 | Gain on Disposal (P+L Acc) | 20,000 Cr |

The transaction flow of Disposal of non current Asset

Below is the disposal account, which represents the entity that has purchased the bus. It clearly shows a credit balance of EUR 20,000, representing a gain for the entity. This gain must be transferred to the Income Statement (Profit and Loss account)

| Date | Jn | Details | Debit | Credit | Balance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2026-12-31 | 5 | Bus Cost Account | 110,000 Dr | 110,000 Dr | |

| 2026-12-31 | 6 | Bus Accumulated Depreciation | 60,000 Cr | 50,000 Dr | |

| 2026-12-31 | 7 | Bank | 70,000 Cr | 20,000 Cr | |

| 2026-12-31 | 8 | Gain on Disposal (P+L Acc) | 20,000 Dr | 0 |

Disposal in part exchange for a new asset

Trading in an asset with a supplier as part exchange for a new asset is a common practice, particularly with vehicles. However, it creates a complex accounting situation that students may initially find challenging to understand—though this difficulty typically resolves as they study and become familiar with the procedure.

In this scenario an asset may be part way through or at the end of its useful economic life and it is exchanged with a dealer for a new vehicle, it obviously will not be worth the same as the brand-new vehicle but it will be worth a fraction of the vehicle. The business then pays the remaining amount owed on the new vehicle in cash.

Take are original example of the bus being sold for EUR 70,000, lets modify this by saying the bus will be part exchanged for EUR 40,000 on a new bus with a price of EUR 130,000 and the remainer being paid for by bank transfer. The journal entries to deal with this situation are the following

This journal represents the sale of the bus (physical removal) to the third party (disposal account)

| Date | Jn No | Details | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2026-12-31 | 5 | Bus Disposal Account | 110,000 Dr | |

| 2026-12-31 | 5 | Bus Cost Account | 110,000 Cr |

This journal entry represents the removal of the accumulated depreciation which must be reflected in the disposal account as it is necessary to reflect the net book value of the bus

| Date | Jn No | Details | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2026-12-31 | 6 | Bus Accumulated Depreciation | 60,000 Dr | |

| 2026-12-31 | 6 | Bus Disposal Account | 60,000 Cr |

This journal entry reflects the dealer Selling/Physical supplying the brand-new bus. So, imagine the new bus being delivered to the business for use. Also be aware that it also represents the Price agreed for the new vehicle.

| Date | Jn No | Details | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2026-12-31 | 9 | Bus Cost Account | 130,000 Dr | |

| 2026-12-31 | 9 | Disposal Account | 130,000 Cr |

This journal entry represents the cash payment element for the bus, this is not the cost of the bus however it is just the cash element, the cost/price of the new bus is EUR 130,000.

| Date | Jn No | Details | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2026-12-31 | 10 | Disposal Account | 90,000 Dr | |

| 2026-12-31 | 10 | Bank | 90,000 Cr |

This journal entry represents the loss on the trade-in of the old vehicle for the new one. It is recorded in the a

nominal account to measure the loss from the transaction.

| Date | Jn No | Details | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2026-12-31 | 11 | Loss on Disposal (P+L) | 10,000 Dr | |

| 2026-12-31 | 11 | Disposal Account | 10,000 Cr |

As you can see, journal entries 5 and 6 document the old bus being delivered to and sold to the dealership, resulting in a balance of EUR 50,000. Journal entry number 9 records the new bus being purchased and delivered to the business. This transaction involves two vehicles moving in opposite directions: one to the dealership and one to the business.

The Net Book Value (NBV) of the old bus is EUR 50,000, and the cost of the new bus is EUR 130,000. This results in a net amount of EUR 80,000 due. However, the dealership requires an additional EUR 90,000 in cash. After paying this cash, we are left with a debit balance of EUR 10,000 with the dealership.

This does not mean the dealership owes us EUR 10,000. Instead, this balance represents an amount we will not recover, indicating it must be written off as a loss. This loss represents the shortfall from the sale of the old bus compared to the cost of acquiring the new bus.

This version aims to clarify the financial transactions and the resulting accounting entries more precisely.

| Date | Jn | Details | Debit | Credit | Balance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2026-12-31 | 5 | Bus Cost Account | 110,000 Dr | 110,000 Dr | |

| 2026-12-31 | 6 | Bus Accumulated Depreciation | 60,000 Cr | 50,000 Dr | |

| 2026-12-31 | 9 | Bus Cost Account | 130,000 Cr | 80,000 Cr | |

| 2026-12-31 | 10 | Bank | 90,000 Dr | 10,000 Dr | |

| 2026-12-31 | 11 | Loss on Disposal (P+L) | 10,000 Cr | 0 |

Change in accounting estimate

It is possible for a business to change its accounting estimate regarding a non-current asset’s economic life, depreciation method, or residual value during the asset’s useful life. It is important to note that this change does not constitute an error in the previous year’s depreciation; rather, it is simply a revision of the estimate. Therefore, no restatement of prior profits is necessary

As an example, our business buys a machine that we estimate will last 5 years with no residual value and we choose the straight-line depreciation method. The machine was exchanged for EUR 25,000 in cash. At the end of year two we realise that the machine will actually last for 7 years not 5 and we will adjust our depreciation charges accordingly. In this case there has already been EUR 25,000 / 5 x 2 = EUR 10,000 depreciation charged and a balance of EUR 10,000 in the accumulated depreciation account. The remaining charge over the five years will change from EUR 5,000 to EUR 3,000. Please examine the depreciation schedule below

| Year | Depreciation Charge | Accumulated Depreciation | Asset Cost | Carrying Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 5,000 Dr | 5,000 Cr | 25,000 Dr | 20,000 Dr |

| 2025 | 5,000 Dr | 10,000 Cr | 25,000 Dr | 15,000 Dr |

| 2026 | 3,000 Dr | 13,000 Cr | 25,000 Dr | 12,000 Dr |

| 2027 | 3,000 Dr | 16,000 Cr | 25,000 Dr | 9,000 Dr |

| 2028 | 3,000 Dr | 19,000 Cr | 25,000 Dr | 6,000 Dr |

| 2029 | 3,000 Dr | 22,000 Cr | 25,000 Dr | 3,000 Dr |

| 2030 | 3,000 Dr | 25,000 Cr | 25,000 Dr | 0 |

Change in accounting estimate

A fixed asset register is a tool for any organisation that aims to manage its tangible and intangible assets more effectively. This system catalogs all fixed assets, providing detailed information on each, including acquisition dates, costs, locations, depreciation rates, and current values. The necessity of a fixed asset register lies in its numerous benefits for financial management, operational efficiency, and compliance.

Firstly

a fixed asset register aids in accurate financial reporting. By maintaining a detailed and up-to-date record of all fixed assets, businesses can ensure that their balance sheets reflect the true value of these assets.

Secondly

it enhances asset management. A fixed asset register allows organizations to track the location, condition, and usage of assets, thereby facilitating better maintenance and utilization. This helps in extending the lifespan of assets, optimizing their performance, and reducing operational costs. Additionally, it aids in identifying underutilized or obsolete assets that can be disposed of or repurposed.

Thirdly

it ensures compliance with regulatory requirements. Many jurisdictions mandate businesses to maintain detailed records of their fixed assets for tax purposes and audits. A fixed asset register helps in meeting these legal obligations, avoiding penalties, and ensuring transparency in financial practices.

A fixed asset register is more “user-friendly” for keeping track of the location and number of assets compared to non-current asset ledger accounts, such as cost and accumulated depreciation, because it provides a detailed, organised, and easily accessible record of each individual asset. Unlike ledger accounts that primarily focus on financial data, the fixed asset register includes critical non-financial information, such as physical location, asset condition, responsible personnel, and unique identification numbers. This comprehensive view allows users to quickly identify and locate assets, manage maintenance schedules, and ensure accountability. The structured format of a fixed asset register simplifies asset management by presenting data in a clear manner, facilitating better decision-making and operational efficiency without the need to sift through extensive financial entries.

Depreciation in manufacturing

Depreciation incurred during the operation of machinery directly used in production presents an additional complexity, as the depreciation expense is added to the cost of the finished goods produced during the manufacturing process.

For instance, if a machine is used to turn apples and syrup into jars of applesauce, the depreciation expense for this machine must be allocated as a small additional cost to each jar of applesauce produced. If the annual depreciation on the machine is EUR 20,000 and the machine produces 20,000 jars of applesauce in a year, each jar would incur an additional cost of EUR 1. This cost is only recognized in the Cost of Sales account when a jar is sold, reflecting an economic measurement of the expense. While this concept may be challenging to visualize, it is logical, as the depreciation can be directly attributed to the stock produced.

Conclusion

In conclusion, understanding depreciation is essential for anyone involved in the financial management of a business. We’ve explored how depreciation serves as a method to account for the inevitable decline in the value of assets over time due to various factors like wear and tear, obsolescence, and usage. By employing methods such as Straight-Line, Reducing Balance, Units of Production, and Sum of the Years’ Digits, businesses can allocate the cost of their assets in a way that reflects their economic benefits over time.

We’ve seen how this process not only affects the balance sheet through asset valuation but also directly impacts the income statement via depreciation expense. Moreover, the disposal or exchange of assets highlights the practical implications of these calculations, showing how businesses must manage gains or losses from such transactions.

The importance of maintaining an accurate fixed asset register cannot be overstated, as it supports effective asset management, compliance with regulatory requirements, and ensures that financial statements reflect the true state of the company’s resources.

Finally, in manufacturing, we recognise that depreciation is not merely an accounting entry but a cost that permeates through to the products themselves, affecting the cost of goods sold when those products are finally sold. This document aims to demystify these concepts, providing a foundation for both students and practitioners to apply in real-world scenarios, ensuring that businesses can make informed decisions about their long-term assets while adhering to the principles of accurate and transparent financial reporting.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

About Us

Legal

Copyright ©2024 Accounting Training. All Rights Reserved

Course Outline

- Concepts and Accounting

- The Three Different Natures of Accounts

- The Accounting Equation

- Accrual Accounting

- Debits and Credits

- The Journal

- Bank Reconciliation

- Adjusting Entries

- Inventory and Cost of Sales

- Depreciation

- Income Statement

- Chart of Accounts

- Accounting Principles

- Financial Accounting

- Financial Statements

- Balance Sheet

- Working Capital and Liquidity

- Cash Flow Statement

- Financial Ratios

- Accounts Receivable and Bad Debts Expense

- Accounts Payable

- Inventory and Cost of Goods Sold

- Payroll Accounting

- Bonds Payable

- Stockholders’ Equity

- Present Value of a Single Amount

- Present Value of an Ordinary Annuity

- Future Value of a Single Amount

- Nonprofit Accounting

- Break-even Point

- Improving Profits

- Evaluating Business Investments

- Manufacturing Overhead

- Nonmanufacturing Overhead

- Activity Based Costing

- Standard Costing