Inventory and Cost of Sales

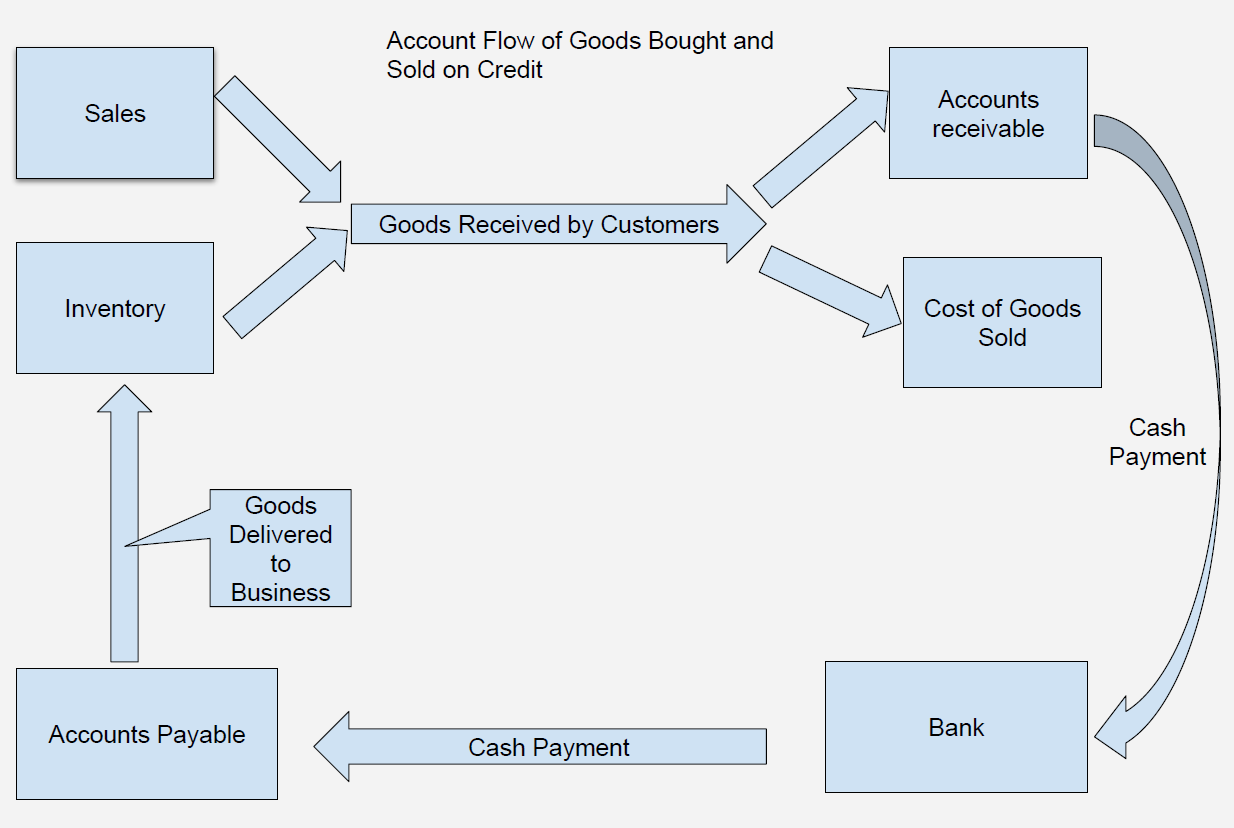

In accounting, there is a close relationship between Inventory and Cost of Sales, as these two accounts are interrelated and interact continuously in the course of business operations. The Inventory account represents the physical stock in financial terms, providing a monetary representation of the goods a business holds for resale. Typically, inventory is valued at the cost at which it was purchased from the supplier.

The Cost of Sales account (also known as the Cost of Goods Sold account) is a nominal account that records the cost incurred by the business when goods are delivered to a customer as part of a sale or when a customer takes the goods from the business premises as a result of a sale. One of the most fundamental relationships between the Inventory account and the Cost of Sales account is that the Inventory account is “credited” when goods are sold and leave the business, while the Cost of Sales account is “debited” to reflect this cost. Similar to Cash, Inventory is a “real” account—when inventory decreases, it is credited, and when it increases, it is debited

In accounting, Cost of Sales and Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) mean the same thing—they’re just different names for the direct costs of producing or buying the products a business sells. Whether it’s materials, labour, or inventory costs, both terms cover the expenses tied to generating sales. The choice of term often depends on the industry or company, but they’re interchangeable in practice

The relationship between the Inventory account and the Cost of Sales account is essential for accurately reflecting a business’s financial position and performance. Let’s break down this relationship further to understand how they interact within the context of accounting principles:

Inventory Account

- Nature: Inventory is considered a “Real” account. It represents the monetary value of goods a business has on hand for resale. This value is typically recorded at the cost at which the goods were purchased from suppliers.

- Accounting Treatment:

- Debit: When inventory is acquired (either through purchase or production), the Inventory account is debited, increasing the asset.

- Credit: When goods are sold and leave the business premises, the Inventory account is credited, reducing the asset.

Cost of Sales (Cost of Goods Sold) Account

- Nature: The Cost of Sales account is a “Nominal” account. It captures the direct costs attributable to the production of the goods sold by a business or the purchase price of these goods. These costs include the cost of materials and direct labour.

- Accounting Treatment:

- Debit: When goods are sold, the Cost of Sales account is debited to reflect the cost associated with the goods that have been delivered to the customer.

- Credit: Typically, this account is credited when adjusting entries are made or to offset purchase returns, but under normal circumstances, it is mainly debited.

Interaction Between Inventory and Cost of Sales

- Recording Purchases: When inventory is purchased, the transaction is recorded as:

- Debit: Inventory (increases asset)

- Credit: Accounts Payable or Cash (increases liability or decreases asset)

- Recording Sales: When inventory is sold, two entries are made:

- Revenue Recognition:

- Debit: Accounts Receivable or Cash (increases asset)

- Credit: Sales Revenue (increases income)

- Cost Recognition:

- Debit: Cost of Sales (increases expense)

- Credit: Inventory (decreases asset)

- Revenue Recognition:

Example Transaction

Let’s consider an example where a business purchases inventory for $1,000 and later sells it for $1,500.

- Purchase of Inventory:

- Debit: Inventory $1,000

- Credit: Accounts Payable $1,000

- Sale of Inventory:

- Revenue Recognition:

- Debit: Accounts Receivable $1,500

- Credit: Sales Revenue $1,500

- Cost Recognition:

- Debit: Cost of Sales $1,000

- Credit: Inventory $1,000

- Revenue Recognition:

The interaction between the Inventory account and the Cost of Sales account is crucial for accurately tracking and reporting the cost associated with goods sold. This relationship ensures that when inventory is sold, the reduction in inventory is matched with the recognition of the cost in the Cost of Sales account, providing a clear picture of the business’s profitability and inventory levels.

In essence, every sale transaction involves:

Debiting Cost of Sales: Reflecting the cost of goods that are no longer in inventory.

Crediting Inventory: Reducing the inventory to account for the goods sold.

This relationship maintains the integrity of financial records and ensures compliance with accounting standards, allowing for accurate financial reporting and analysis.

Valuation of Inventory

Inventory is valued at its purchase price, along with any incidental costs incurred to bring it to its current state and condition. For example, if a business purchases goods at a cost of EUR 10 per unit and incurs an additional transportation cost of EUR 0.50 per unit, the goods will be recorded at a total cost of EUR 10.50 per unit in the inventory account. Essentially, goods held for resale are recorded at cost in the inventory account.

However, in rare circumstances, the goods in the inventory account may actually sell for less than their cost. This is obviously a bad commercial situation for a business, and as a business owner, you would not want this to happen too often, or you could go out of business. When this situation occurs, the accounting concept of prudence (or conservatism) comes into play, and the business is obliged to write down the stock to “Net Realisable Value.” This means that the inventory must be valued at market value.

In summary, inventory is valued in a business in two main ways

- Cost (the most usual)

- Net Realisable Value (Rarer)

Types of Inventory: An Overview

- Raw Materials

- Work in Progress (WIP)

- Finished Goods

These classifications are essential for understanding how different types of inventory are managed and valued within various types of businesses, particularly manufacturing versus retail.

Raw Materials

Raw Materials are the basic inputs that are used to produce goods. They are the unprocessed substances that will eventually be transformed through the manufacturing process into finished products. Examples include metals, wood, chemicals, and textiles. For manufacturing companies, managing raw materials efficiently is crucial as they form the foundation of the production process.

Work in Progress (WIP)

Work in Progress (WIP) refers to partially completed goods that are still in the production process. These items have started their journey through the manufacturing process but are not yet ready to be sold as finished products. WIP includes everything from the initial raw materials that are currently being processed to the labour and overhead costs associated with their production.

Valuing Raw Materials and Work in Progress

In manufacturing businesses, valuing inventory can become complex due to the transitions raw materials undergo to become finished goods. Accurate valuation is critical for financial reporting and cost management. Costs directly associated with manufacturing, such as labour, materials, and overhead, must be allocated to the cost of goods produced.

Example: Electricity Usage

Consider a machine that transforms raw materials into work in progress. This machine consumes a specific amount of electricity for each batch of materials it processes. The cost of this electricity can be measured and added to the cost of the units produced. This allocation of direct costs, such as electricity, to the WIP inventory ensures that the expense is recognized correctly in the cost of goods sold (COGS) once the finished product is sold.

Finished Goods

Finished Goods are the completed products ready for sale to customers. These items have passed through the entire manufacturing process and are now available for distribution, marketing, and sale. For retailers or wholesalers, finished goods are the primary form of inventory, as they typically do not engage in the manufacturing process themselves.

Simplified Inventory Valuation for Resellers

In this chapter, we will focus on organizations that purchase finished goods for resale with minimal modifications. For these businesses, inventory management is generally less complex compared to manufacturers. They buy products that are already finished and ready for sale, hence the inventory valuation involves:

- Purchase Cost: The price paid to acquire the finished goods.

- Freight and Handling: Costs associated with transporting the goods to the warehouse or store.

- Minor Modifications: Any small changes or packaging done before the goods are sold.

Understanding the types of inventory and their valuation is essential for effective inventory management and accurate financial reporting. While manufacturing businesses deal with the complexity of valuing raw materials and work in progress, retail and wholesale businesses primarily manage finished goods.

The Purchases Account – A Difficult Account to Understand

In accounting texts, when a company purchases goods for resale, they are often debited to the “Purchases” account. However, the name of this chapter is “Inventory and Cost of Sales.” I’ve just explained earlier in this chapter that when an item of stock leaves inventory, it becomes a cost in the Cost of Sales (Cost of Goods Sold) account. So, what’s this “Purchases” account? Is that just another term for “Cost of Sales” account? No, this is a confusing thing about the inventory-cost of sales cycle because inventory is often valued only once a year (Periodic Inventory System, more about this later). Therefore, a business doesn’t know its inventory valuation at any particular time during the year.

The Role of the Purchases Account

As a result of this, and as a practical matter, whenever a business buys goods for resale, it credits bank/cash or accounts payable and debits the “Purchases” account. This approach simplifies the recording process during the year but can cause confusion when trying to understand the relationship between purchases, inventory, and cost of sales.

Classification Challenges

The Purchases account does not fit neatly into any of the standard account types. It’s not nominal, as it doesn’t represent the usage or expiry of goods. It’s not a real account, since it does not represent the existence of inventory (the Inventory account fulfils that function). It’s not a personal account either, as it doesn’t represent the entity supplying the goods (that’s the Accounts Payable account). This uniqueness often leads to confusion for those new to accounting.

A Practicality in the Periodic Inventory System

The Purchases account is necessary in a periodic inventory system, where inventory is only counted once a year. In such a system, businesses do not keep continuous, up-to-date records of inventory levels. Instead, they rely on periodic physical counts to determine the ending inventory balance. Between counts, the Purchases account records all goods bought for resale, providing a straightforward way to track inventory inflows.

Transitioning to Cost of Sales

At the end of the accounting period, the balance in the Purchases account is combined with the beginning inventory balance and any additional costs to calculate the cost of goods available for sale. From this, the ending inventory is subtracted (determined by the physical count), resulting in the cost of goods sold (COGS). The formula can be summarized as:

Cost of Sales (COGS)=Beginning Inventory+Purchases−Ending Inventory

Benefits of Understanding the Purchases Account

The “purchases” account is a bit of a tricky one, and that’s what makes it so interesting! It doesn’t fit neatly into the usual categories of real, personal, or nominal accounts, which can feel confusing at first. But that’s actually a good thing—it gives you a chance to gain a deeper insight into how the periodic inventory system works. By understanding why the purchases account is unique (it tracks the flow of inventory into the business rather than being a straightforward asset, liability, or expense), you’ll start to see the bigger picture of why it is closed out to the trading account.

Modern Practices

In contemporary accounting, many businesses have shifted to perpetual inventory systems, which maintain continuous records of inventory levels. In such systems, the Purchases account is replaced by direct entries to the Inventory account. This approach reduces the end-of-year adjustments and provides real-time inventory data, enhancing accuracy and decision-making capabilities.

While the Purchases account may seem confusing at first, especially within the periodic inventory system, it serves a vital role in tracking the flow of goods into a business. By understanding its purpose and how it integrates into the overall accounting cycle, students will have a clear comprehension of why it is used as an item in the trading account. The shift towards perpetual inventory systems is reducing reliance on the Purchases account, but its understanding remains fundamental for those dealing with periodic inventory systems.

The Trading Account, the Purchases Account and the Periodic Inventory System

The Income Statement is essentially a summary of two key accounts prepared by a business at the end of the fiscal year: the Trading Account and the Profit and Loss Account. These two serve different but complementary purposes. The Trading Account focuses on calculating and summarizing the direct costs tied to the sales of the business—costs that are definitively caused by or linked to a sale. For instance, if a customer buys a piece of furniture from a furniture store, the business knows exactly how much it paid the supplier for that specific piece. This cost arises directly because the inventory item has left the store, is now in the customer’s possession, and can no longer benefit the business. Such direct costs are recorded in the Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) line in the Trading Account, capturing the immediate financial outflow tied to generating sales. This distinction is crucial for understanding how businesses measure their gross profit before considering other operating expenses.

An example of an indirect cost would be the electricity usage in the furniture store, that would appear in the Profit and Loss account.

Back to our periodic inventor system, the business doesn’t know on a day-to-day basis how much stock it has in its inventory, it does know at the end of the year when it performs its stock count. One of the reasons it has to do its stock count at the yearend is the fact that it is obligated to produce its yearend financial statements of which the “Trading” account is a fundamental part.

So how does the business calculate the “Cost of Sales” or “Cost of Goods Sold” if it hasn’t been keeping a record during the year on what has left the stock room in sales to the customer? Well, what does it know? It knows the stock levels at the beginning of the year, this is from last year’s stock count, it knows how much stock flowed into the business during the year as it has debited all of this to the “Purchases” account and it knows how much of this stock remained in the inventory at the end of the year.

Therefore, if we know how much inventory was there at the beginning, how much inventory flowed into the stock room during the year and we know how much was there at the end of the year, we have a reasonably simple calculation to find out what flowed out of the stock room in to the hands of paying customers during the year.

The beginning inventory (goods that have been sold during the year) + Purchases (the flow of goods for resale into the business during the year) – The ending inventory (goods for resale that we know definitely have not been sold) = Cost of Sales (GOGS) (The flow of goods out in paying customers hands)

Lets look at an example of the trading account

Trading Account

This is the Trading Account, it is the first component of the Income Statement, the second part being the Profit and Loss account. The following are the end of year journal entries that constitute the Trading Account.

| Date | Detail | Jn No. | Debit | Credit | Balance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024-12-31 | Sales | 1 | 100,000 Cr | 100,000 Cr | |

| 2024-12-31 | Inventory | 2 | 15,000 Dr | 85,000 Cr | |

| 2024-12-31 | Purchases | 3 | 70,000 Dr | 15,000 Cr | |

| 2024-12-31 | Inventory | 4 | 20,000 Cr | 35,000 Cr |

This journal entry reflects the incorporation of the Sales value into the Trading account at year-end. The Sales value represents the goods and services successfully delivered to customers, valued based on what the customer has paid or will pay. When reviewing this figure, envision goods and services being delivered to customers throughout the fiscal year—from the first to the last day. It is important to note that the Sales figure represents the flow of goods and services, not cash flows.

| Date | Account | Jn No. | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024-12-31 | Sales | 1 | 100,000 Dr | |

| 2024-12-31 | Trading | 1 | 100,000 Cr |

This journal entry represents the removal of the previous year’s stock valuation, that is the process of counting the inventory and valuing it according to its original purchase price. The assumption being that this inventory has been sold by the year end.

| Date | Account | Jn No. | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024-12-31 | Trading | 2 | 15,000 Dr | |

| 2024-12-31 | Inventory | 2 | 15,000 Cr |

As discussed earlier the purchases account is an unusual account in that it doesn’t fit into any of the general natures (real, personal or nominal). It in practical terms it represents the physical flow of goods into the firm’s inventory room from suppliers measured at the value that those good were exchanged for from the supplier. This journal entry assumes that all these goods were sold during the year however we know this is not the case as there is inventory remaining at the yearend, but this factor is corrected in the next journal entry.

| Date | Account | Jn No. | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024-12-31 | Trading | 3 | 70,000 Dr | |

| 2024-12-31 | Purchases | 3 | 70,000 Cr |

This is the final journal entry into the yearend Trading account. This entry is the result of the yearend inventory count that the staff does in a periodic inventory system. This journal entry achieves two very important objectives

- It gives an accurate value for the yearend inventory figure listed on the balance sheet

- It corrects the figure for Cost of Sales in the Trading account, removing any remaining inventory from the calculation of goods sold to the public during the year.

| Date | Account | Jn No. | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024-12-31 | Inventory | 4 | 20,000 Dr | |

| 2024-12-31 | Trading | 4 | 20,000 Cr |

In our example the business sells goods to the public of EUR 100,000 and has an opening inventory of EUR 15,000 and a purchases figure of EUR 70,000 and a closing inventory figure of EUR 20,000.

Therefore, the cost of sales will be the following: Opening inventory EUR 15,000 + Purchases EUR 70,000 – Closing Inventory EUR 20,000 = Cost of Sales EUR 65,000

Interesting note: what is the ending balance on the trading account called? It’s the gross profit, yes, the gross profit is actually a balance and not just the result of a subtraction. Here is the trading account done in a more presentable format that you would see at the beginning of the Income Statement

Income statement (Trading Account Section) of Fictitious Business Y/E 2024-12-31

| EUR | EUR | |

|---|---|---|

| Sales | 100,000 | |

| Less | ||

| Opening Inventory | 15,000 | |

| Purchases | 70,000 | |

| Closing Inventory | (20,000) | |

| Cost of Sales | (65,000) | |

| Gross Profit | 35,000 |

Notice now the balance is actually represented as a Sub total. This is the usual format that you will see a trading account but please remember, the trading account is an account that follows the same rules like any other.

Perpetual and Periodic Inventory Systems

Periodic Inventory System

As alluded to earlier, there is the “Periodic” inventory system, which essentially means that the business does not know what its inventory valuation is at any particular time. It can only establish this fact when it performs an inventory count, which can be very disruptive and labour-intensive, so they are typically done only once a year. The purchase account plays a big role as the invoices from the suppliers will give lots of important information about how much the inventory costs, etc., as they don’t have a system sophisticated enough to provide them with current inventory valuations and components.

Perpetual Inventory System

The perpetual inventory system is much more sophisticated than the periodic system. A business knows exactly how much stock it has at any given time and can dispense with the “purchases” account and just debit the inventory account directly. An example of this would be a jeweller, as they have very expensive and specific stock in that type of business.

Specific Example:

Consider a jewellery store using a perpetual inventory system. When the store purchases a new diamond ring for €5,000, the inventory account is updated immediately. If the store sells the ring for €8,000, the inventory is decreased, and the cost of goods sold is recorded instantly.

Double Entry Example:

| Date | Account | Debit (€) | Credit (€) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purchase | Inventory | 5,000 | |

| Accounts Payable | 5,000 | ||

| Sale | Accounts Receivable | 8,000 | |

| Sales Revenue | 8,000 | ||

| Sale | Cost of Goods Sold | 5,000 | |

| Inventory | 5,000 |

Further Insights

- Advantages of Periodic Inventory System:

- Simplicity and lower initial setup costs.

- Suitable for small businesses with less complex inventory systems.

- Disadvantages of Periodic Inventory System:

- Lack of real-time inventory data.

- Potential for discrepancies and errors due to infrequent counts.

- More labour-intensive during physical counts.

- Advantages of Perpetual Inventory System:

- Provides real-time inventory data, aiding in better decision-making.

- Reduces the need for labour-intensive physical counts.

- Can integrate with other systems (e.g., point-of-sale systems) for seamless operations.

- Disadvantages of Perpetual Inventory System:

- Higher initial setup costs and complexity.

- Requires regular maintenance and updates to ensure accuracy.

- Dependent on technology and software, which can be vulnerable to system failures or cyber-attacks.

By understanding the differences, advantages, and disadvantages of both systems, businesses can choose the inventory management approach that best suits their operational needs and scale.

Cost-Flow Assumptions in Inventory Management

In managing inventory under the periodic system, businesses employ various cost-flow assumptions to determine the cost of goods sold (COGS) and the value of ending inventory. The three main cost-flow assumptions are First-In, First-Out (FIFO), Weighted-Average Cost, and Last-In, First-Out (LIFO).

First-In, First-Out (FIFO)

FIFO assumes that the oldest inventory items are sold first. This method aligns closely with the natural flow of goods, making it a widely adopted practice. Under FIFO, the cost of the earliest items purchased is assigned to COGS, while the cost of the latest purchases remains in ending inventory.

Example:

A company purchases 100 units of inventory at €10 each in January, 100 units at €12 each in February, and 100 units at €14 each in March. If the company sells 150 units by year-end, under FIFO, the COGS would be calculated as follows:

- 100 units at €10 = €1,000

- 50 units at €12 = €600

Total COGS = €1,600

The remaining inventory would be:

- 50 units at €12 = €600

- 100 units at €14 = €1,400

- Total Ending Inventory = €2,000

Weighted-Average Cost

The weighted-average cost method calculates the average cost of all inventory items available during the period and applies this average cost to both COGS and ending inventory. This method smooths out price fluctuations over the period.

Example:

Using the same purchases as the FIFO example, the weighted-average cost per unit would be:

(Insert Weighted Average Cost)

= EUR 3,600/300 Units = EUR 12 = Weighted Average Cost

If 150 units are sold, the COGS would be:

150 Units Sold(Delivered to Customer) x EUR 12 = EUR 1,800

The ending inventory would be:

150 unit in Inventory at yearend x EUR 12 = EUR 1,800

Antiquated Nature of LIFO

LIFO is considered antiquated and less logical because it does not reflect the actual physical flow of inventory. Most businesses sell their oldest inventory first, making FIFO a more natural and intuitive method. Additionally, LIFO can result in outdated inventory values being reported on the balance sheet, leading to less accurate financial statements.

Despite its shortcomings, LIFO remains in use in the United States due to its favourable tax implications. During periods of rising prices, LIFO results in higher COGS and lower taxable income, providing a tax advantage. However, this benefit is offset by the complexity of maintaining LIFO records and the potential for outdated inventory values.

In conclusion, while the periodic inventory system is suitable for smaller businesses, the choice of cost-flow assumption—FIFO, weighted-average cost, or LIFO—can significantly impact financial reporting and tax liabilities. FIFO and weighted-average cost are more reflective of actual inventory usage, whereas LIFO persists mainly for its tax benefits in the U.S., despite its logical and practical limitations.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

About Us

Legal

Copyright ©2024 Accounting Training. All Rights Reserved

Course Outline

- Concepts and Accounting

- The Three Different Natures of Accounts

- The Accounting Equation

- Accrual Accounting

- Debits and Credits

- The Journal

- Bank Reconciliation

- Adjusting Entries

- Inventory and Cost of Sales

- Depreciation

- Income Statement

- Chart of Accounts

- Accounting Principles

- Financial Accounting

- Financial Statements

- Balance Sheet

- Working Capital and Liquidity

- Cash Flow Statement

- Financial Ratios

- Accounts Receivable and Bad Debts Expense

- Accounts Payable

- Inventory and Cost of Goods Sold

- Payroll Accounting

- Bonds Payable

- Stockholders’ Equity

- Present Value of a Single Amount

- Present Value of an Ordinary Annuity

- Future Value of a Single Amount

- Nonprofit Accounting

- Break-even Point

- Improving Profits

- Evaluating Business Investments

- Manufacturing Overhead

- Nonmanufacturing Overhead

- Activity Based Costing

- Standard Costing