The Income Statement

A Comprehensive Guide for Accounting Students

The income statement, often referred to as the profit and loss statement, is a cornerstone document in financial accounting. It provides a detailed summary of an organisation’s financial performance over a specific period, typically one fiscal year. Unlike the balance sheet, which presents a snapshot of financial position at a point in time, the income statement reflects the dynamic nature of business operations, capturing the revenues earned and expenses incurred during the accounting period. This document is not part of the double-entry system but is constructed using accounts that are integral to it. Its ultimate aim is to determine the net profit or loss of the organisation, representing either an increase or decrease in equity during the period under review.

Components of the Income Statement

Nominal Accounts: The Building Blocks

The income statement is exclusively composed of nominal accounts, which include revenues, expenses, gains, and losses. These accounts are temporary in nature, meaning their balances are closed to the trading and profit and loss accounts at the end of the accounting period. Nominal accounts do not represent cash flows; instead, they capture the value created or consumed in delivering goods and services to customers. This accrual-based approach emphasises the cause-and-effect relationship between revenues and expenses, distinguishing the income statement from a cash flow statement.

Trading Account and Profit and Loss Account

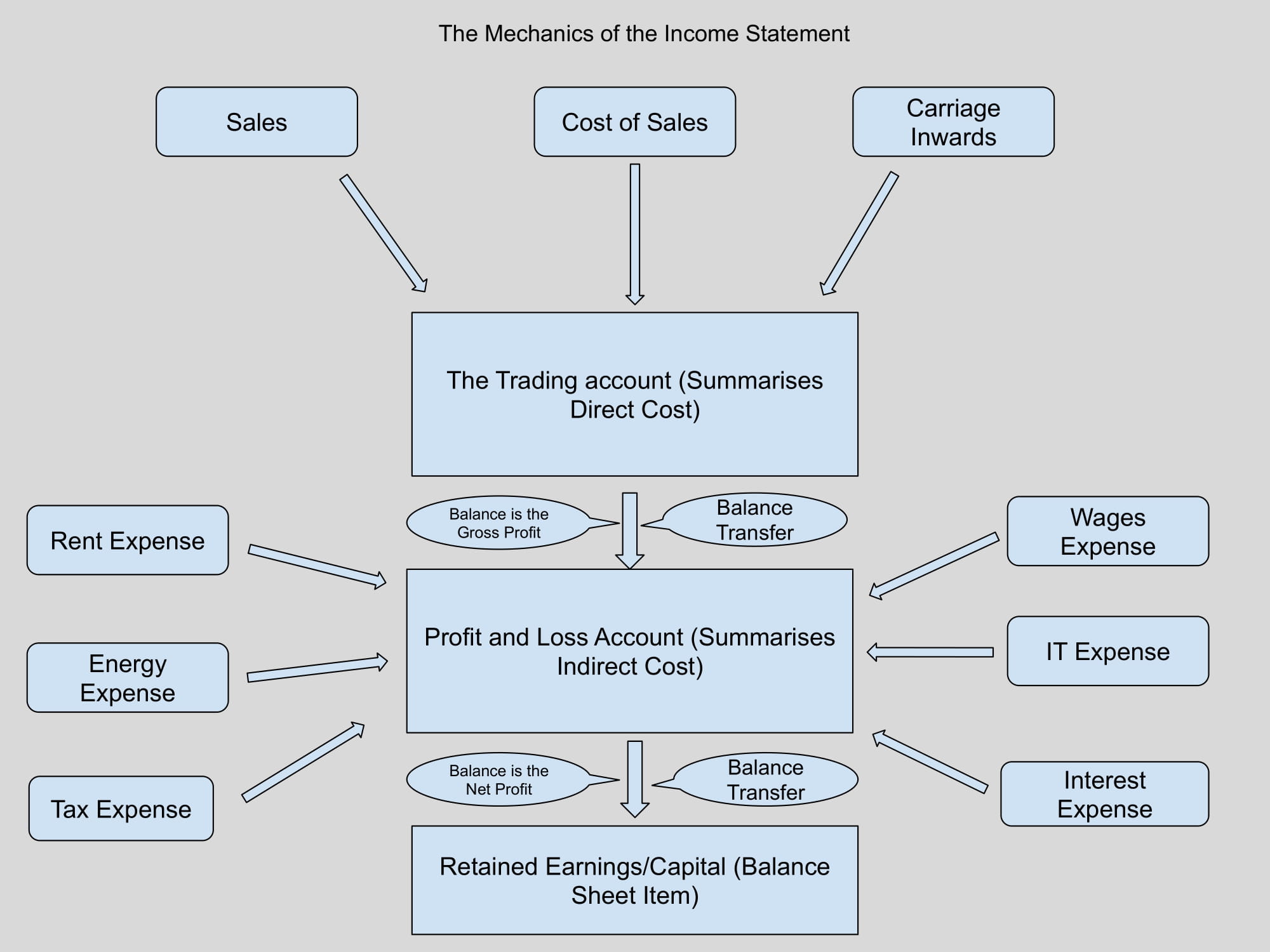

The income statement can be broadly divided into two sections:

1. Trading Account:

- The trading account focuses on direct costs associated with sales, such as cost of goods sold (COGS).

- Key components include:

- Opening stock

- Purchases

- Closing stock

- The formula for calculating gross profit is:

Gross Profit = Sales Revenue – Cost of Sales

Important: The Trading account summarises the DIRECT COSTS associated with the sales or revenue of an organisation. - For businesses using a perpetual inventory system, the cost of sales account is closed directly to the trading account. The resulting balance is the gross profit, which is then transferred to the profit and loss account.

2. Profit and Loss Account:

- The profit and loss account begins with the gross profit carried over from the trading account.

- It includes all indirect expenses and income that are not directly tied to sales, such as:

- Rent, wages, and salaries

- Depreciation

- Utility costs

- Postage and stationery

- IT and administrative expenses

- Non-operating gains or losses (e.g., rent income, gain or loss on the sale of non-current assets)/li>

- The balance on this account undergoes several stages, representing:

- Operating profit (gross profit minus operating expenses)

- Profit before interest and tax (PBIT)

- Profit before tax (PBT)

- Net profit or net earnings (after tax and interest adjustments)

Important: The Profit and Loss Account summarises the INDIRECT COSTS associated with the Sales or Revenues of an organisation.

Journal Entries and the Closing Process

At the close of the fiscal year, all nominal accounts are closed off or their balances transferred to the trading and profit and loss accounts. These journal entries are typically dated the last day of the accounting period but are often executed post-year-end using computerized accounting systems. This process ensures that the nominal accounts are reset to zero for the new accounting period, ready to capture the next cycle of financial performance.

Please see the example below of the Journal and accounting process of the income statement. It is entirely composed of nominal accounts and is mechanical in its operation.

Below are the raw journal entries that clear the balance of all the nominal accounts on the trial balance. These are all dated on the last instant of the fiscal year.

| Date | Jn No | Details | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024-12-31 | 1 | Sales Acc | 500,000 Dr | |

| 2024-12-31 | 1 | Trading Acc | 500,000 Cr | |

| 2024-12-31 | 2 | Trading Acc | 250,000 Dr | |

| 2024-12-31 | 2 | Cost of Sales (COGS) | 250,000 Cr | |

| 2024-12-31 | 3 | Trading Acc | 250,000 Dr | |

| 2024-12-31 | 3 | Profit and Loss Acc | 250,000 Cr | |

| 2024-12-31 | 4 | Rent Exp Acc | 20,000 Dr | |

| 2024-12-31 | 4 | Profit and Loss Acc | 20,000 Cr | |

| 2024-12-31 | 5 | Depreciation Exp Acc | 30,000 Dr | |

| 2024-12-31 | 5 | Profit and Loss Acc | 30,000 Cr | |

| 2024-12-31 | 6 | Energy Exp Acc | 5,000 Dr | |

| 2024-12-31 | 6 | Profit and Loss Acc | 5,000 Cr | |

| 2024-12-31 | 7 | Wages Exp Acc | 50,000 Dr | |

| 2024-12-31 | 7 | Profit and Loss Acc | 50,000 Cr | |

| 2024-12-31 | 8 | IT Exp Acc | 8,000 Dr | |

| 2024-12-31 | 8 | Profit and Loss Acc | 8,000 Cr | |

| 2024-12-31 | 9 | Profit and Loss Acc | 7,000 Dr | |

| 2024-12-31 | 9 | Gain on Sale of Delivery Van | 7,000 Cr | |

| 2024-12-31 | 10 | Interest Exp Acc | 2,500 Dr | |

| 2024-12-31 | 10 | Profit and Loss Acc | 2,500 Dr | |

| 2024-12-31 | 11 | Tax Exp Acc | 15,000 Dr | |

| 2024-12-31 | 11 | Profit and Loss Acc | 15,000 Dr | |

| 2024-12-31 | 12 | Profit and Loss Acc | 126,500 Dr | |

| 2024-12-31 | 12 | Capital /Retained Earnings | 126,500 Dr |

Trading Account

This is the first component of the Income Statement, the Trading account details the Sales and Cost of Sales (Direct Costs)

| Date | Jn No | Details | Balance Designation | Debit | Credit | Balance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024-12-31 | 1 | Sales Acc | 500,000 Cr | 500,000 Cr | ||

| 2024-12-31 | 2 | Cost of Sales (COGS) | Gross Profit | 250,000 Dr | 250,000 Cr | |

| 2024-12-31 | 3 | Profit and Loss Acc | 250,000 Dr | 0 |

Profit and Loss Account

This is the second component of the Income Statement and it incorporates all the indirect costs which cannot be traced directly back to sales

| Date | Jn No | Details | Balance Designation | Debit | Credit | Balance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024-12-31 | 3 | Trading Acc | 250,000 Cr | 250,000 Cr | ||

| 2024-12-31 | 4 | Rent Exp Acc | 20,000 Dr | 230,000 Cr | ||

| 2024-12-31 | 5 | Depreciation Exp Acc | 30,000 Dr | 200,000 Cr | ||

| 2024-12-31 | 6 | Energy Exp Acc | 5,000 Dr | 195,000 Cr | ||

| 2024-12-31 | 7 | Wages Exp Acc | 50,000 Dr | 145,000 Cr | ||

| 2024-12-31 | 8 | IT Exp Acc | Operating Profit | 8,000 Dr | 137,000 Cr | |

| 2024-12-31 | 9 | Gain on Sale of Delivery Van | Profit before Interest | 7,000 Cr | 144,000 Cr | |

| 2024-12-31 | 10 | Interest Exp Acc | Profit before tax | 2,500 Dr | 141,500 Cr | |

| 2024-12-31 | 11 | Tax Exp Acc | Net Earnings/Profit | 15,000 Dr | 126,500 Cr | |

| 2024-12-31 | 12 | Capital /Retained Earnings | 126,500 Dr | 0 |

Retained Earnings Account

Ultimately the Net Profit or Net Earnings are transferred to the Retained Earnings or Capital account to detail the increase (or potentially a decrease) in the owners claim on the assets of the organisation

| Date | Jn No | Details | Balance Designation | Debit | Credit | Balance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024-01-01 | Opening Balance | 450,000 Cr | ||||

| 2024-12-31 | 12 | Profit and Loss Acc | Opening Balance | 126,500 Cr | 576,500 Cr |

Income Statement for the Y/E 2024-12-31

Now that we have seen how the process of closing off nominal accounts to the Trading Account and Profit and Loss Account works, below is the Income Statement, which serves as a summary of the information in the Trading Account and Profit and Loss Account. It provides a more aesthetically pleasing presentation of the same information however it’s the same information none the less.

| Income Statement for the Y/E 2024-12-31 | EUR |

|---|---|

| Sales | 500,000 |

| Cost of Sales (COGS) | 250,000 |

| Gross Profit | 250,000 |

| Expenses | |

| Rent | 20,000 |

| Energy | 5,000 |

| Wages | 50,000 |

| Infomation Technology | 8,000 |

| Depreciation | 30,000 |

| Operating Profit | 137,000 |

| Gain on Sale of Delivery Van | 7,000 |

| Profit before Interest | 144,000 |

| Interest | 2,500 |

| Profit before Tax | 141,500 |

| Tax | 15,000 |

| Net Earnings | 126,500 |

Significance of Key Subtotals

Each subtotal in the income statement provides valuable insights into the financial health and operational efficiency of the organisation. These subtotals include:

Gross Profit

a. Represents the surplus after direct costs of production or sales are deducted from revenue.

b. Indicates the efficiency of core business operations in generating profit.

Operating Profit

a. Calculated as gross profit minus operating expenses.

b. Reflects the profitability of the organisation's primary business activities, excluding the impact of financing and taxation.

Profit Before Interest

a. Represents earnings before any financing costs are deducted.

b. Useful for evaluating operational efficiency without the influence of capital structure.

Profit After Non-Operating Gains/Losses

a. Incorporates revenues and expenses not related to core operations, such as income from investments or losses on asset disposals.

b. Highlights the impact of ancillary activities on overall profitability.

Profit Before Tax (PBT)

a. Measures profitability after accounting for operating and non-operating activities but before taxation.

b. A critical metric for stakeholders assessing the company's pre-tax earnings capacity.

Net Profit

a. The final line item, representing the ultimate earnings of the organisation after all expenses, including taxes and interest, have been deducted.

b. Indicates the amount available for distribution to shareholders or reinvestment in the business.

The Role of Net Profit in Equity

Once the net profit is determined, it is transferred to the retained earnings or capital account in the equity section of the balance sheet. Retained earnings represent accumulated profits that have not been distributed as dividends and are reinvested in the business. This balance serves as a ceiling for the dividends that shareholders may claim, emphasising the link between the income statement and the broader financial structure of the organisation.

Practical Implications for Accounting Students

Understanding the mechanics and significance of the income statement is crucial for aspiring accountants. Here are some practical takeaways:

Accrual Accounting Principles

a. The income statement reflects accrual accounting, where revenues and expenses are recognized when earned or incurred, not necessarily when cash is exchanged.

Analysis and Interpretation

a. The subtotals and final balances in the income statement provide a framework for analysing operational efficiency, cost management, and profitability.

b. For example, a declining gross profit margin may signal rising production costs or pricing pressures, while consistent operating profit growth indicates effective expense management.

Preparation and Adjustment

a. Familiarity with journal entries for closing nominal accounts and transferring balances to the trading and profit and loss accounts is essential for preparing accurate income statements.

Integration with Other Financial Statements

a. The income statement is intrinsically linked to the balance sheet (via retained earnings) and cash flow statement (via reconciliation of net income to cash flows).

The Difference Between Internal and External Income Statements

The primary distinction between internal and external income statements lies in their intended audience and purpose. Internal income statements are designed for use within the organisation. They serve as tools for management and internal stakeholders to assess the company’s operational performance, identify trends, and guide strategic decision-making. These statements help managers allocate resources efficiently, control costs, and optimise profitability. Internal users, such as department heads, project managers, and executives, require detailed and specific information to monitor performance and make informed decisions.

In contrast, external income statements are prepared for external stakeholders, including investors, creditors, regulators, and the general public. Their primary purpose is to provide a clear, accurate, and standardised overview of the organization’s financial health and performance. External income statements ensure transparency, build trust, and comply with legal and regulatory requirements, such as Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) or International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). Investors and creditors use these statements to assess the company’s profitability, risk profile, and financial stability.

Level of Detail

Another significant difference between internal and external income statements is the level of detail they contain. Internal income statements often include highly detailed and granular information tailored to the organisation’s specific needs. For example, these statements may break down revenues and expenses by department, product line, or geographic region. Managers may also incorporate non-financial metrics, such as operational efficiency or customer satisfaction, to gain a comprehensive understanding of performance. Internal income statements can be customised in format and frequency, such as weekly, monthly, or quarterly reports, to meet the organisation’s requirements.

External income statements, on the other hand, prioritise standardisation and conciseness. They typically follow a prescribed format to ensure compliance with accounting standards and facilitate comparison with other companies. External statements focus on high-level summaries of revenues, expenses, and net income, providing just enough information for stakeholders to evaluate the company’s performance without delving into operational specifics. For example, an external income statement might consolidate expenses into broad categories, such as cost of goods sold (COGS) or selling, general, and administrative expenses (SG&A), rather than itemizing individual costs.

Legal and Regulatory Compliance

Legal and regulatory compliance is another critical distinction between the two types of income statements. External income statements are subject to stringent legal and regulatory standards to ensure accuracy, reliability, and consistency. Companies must adhere to GAAP, IFRS, or other applicable frameworks, depending on their jurisdiction and industry. External income statements are often audited by independent third parties to verify their credibility and prevent fraud. Non-compliance can lead to legal penalties, reputational damage, and loss of investor confidence.

In contrast, internal income statements are not bound by these external regulations. Organisations have the flexibility to design and present internal statements in any format that suits their operational needs. While internal reports must be accurate to support effective decision-making, they are not typically subject to external audits or regulatory oversight. This flexibility allows companies to experiment with innovative reporting methods and focus on metrics that drive internal performance improvement.

Frequency of Preparation

The frequency with which income statements are prepared also varies between internal and external reports. Internal income statements are often generated more frequently to provide real-time insights into the organization’s performance. Managers may require weekly or monthly updates to respond quickly to changes in the business environment.

External income statements, however, are usually prepared quarterly or annually, in line with reporting cycles mandated by regulatory bodies. This less frequent preparation reflects the external stakeholders’ need for periodic updates rather than continuous monitoring.

The Statement of Comprehensive Income

The Statement of Comprehensive Income (SCI) extends the traditional Income Statement by including unrealised gains or losses, as summarised in the Other Comprehensive Income (OCI) section. It is a crucial document because it accounts for all changes in equity not derived from transactions with owners, providing a more comprehensive view of a company’s financial performance.

Key Components

1. Income Statement (Net Profit or Loss)

- This section calculates the profit or loss from core business activities during the reporting period, including:

- Revenue: Income from sales or services.

- Cost of Sales (COGS): Costs directly related to producing goods/services.

- Operating Expenses: Administrative and other operational costs.

- Finance Costs: Expenses like interest on borrowings.

- Net Profit: The final profit after taxes and all expenses.

2. Other Comprehensive Income (OCI)

- OCI captures unrealized gains and losses that affect equity but are not included in net profit because they have not yet been realized. According to the uploaded document:

- These unrealised changes typically arise from the statement of equity or stockholders’ equity.

- These gains/losses cannot be distributed as dividends, as they are not realised, but they must still be accounted for.

- Common examples include:

- Revaluation Surplus: Increases in the value of long-term assets (e.g., property).

- Foreign Currency Translation Adjustments: Fluctuations in exchange rates affecting overseas operations.

- Unrealised Gains/Losses on Financial Instruments: Fair value changes in certain investments.

- Hedging Instruments: Changes in the value of derivatives used to hedge risks.

3. Total Comprehensive Income

The sum of net profit and OCI, representing the total economic gains during the period.

Purpose of the OCI

- The OCI functions as an added layer to the income statement to provide clarity on unrealised gains or losses that:

- Influence the company's financial health.

- Are essential for accurate valuation but do not immediately impact distributable profits.

Presentation of the Statement of Comprehensive Income

1. Single-Statement Approach

Combines net profit and OCI into one continuous document.

2. Two-Statement Approach

Separates the income statement and OCI into two reports.

Example Format

ABC Corporation – Statement of Comprehensive Income for the Year Ended Dec 31, 20XX

| Particulars | Amount (USD) |

|---|---|

| Revenue | 500,000 |

| Less: Cost of Sales | (200,000) |

| Gross Profit | 300,000 |

| Operating Expenses | (100,000) |

| Operating Profit | 200,000 |

| Finance Costs | (30,000) |

| Profit Before Taxt | 170,000 |

| Tax Expense | (40,000) |

| Net Profit | 130,000 |

| Other Comprehensive Incomet | |

| - Revaluation Surplus on Land | 20,000 |

| - Foreign Currency Translation Adjustment | 5,000 |

| Total Comprehensive Income | 155,000 |

Why is the Statement of Comprehensive Income Important?

This document bridges the gap between operational outcomes (profit or loss) and broader financial impacts (unrealized changes), enhancing the financial reporting landscape.

Transparency

Highlights the impact of unrealised gains and losses.

Decision-Making

Assists stakeholders in evaluating risks and future opportunities.

Regulatory Compliance

Ensures all elements affecting equity are documented.

Single-Step and Multi-Step Format

A single-step income statement and a multi-step income statement are two common formats for presenting a company’s financial performance over a specific period. A single-step income statement simplifies reporting by combining all revenues and gains into a single total and subtracting all expenses and losses to determine net income, offering a straightforward view of profitability. In contrast, a multi-step income statement provides a more detailed breakdown, separating operating revenues and expenses from non-operating items, and calculating intermediate figures such as gross profit and operating income. This format is particularly useful for analysing the core operations of a business, as it highlights how well the company generates profit from its primary activities. The choice between these formats often depends on the complexity of the business and the level of detail required by users of the financial statements.

Function and Nature of Expenses

The terms "functions of expenses" and "nature of expenses" refer to two distinct ways of categorising expenses in accounting, each serving different analytical purposes:

Nature of Expenses

The "nature of expenses" classification groups expenses based on their inherent type or what they are. This method focuses on the natural description of the expense without linking it to a specific organisational activity. Examples include salaries, raw materials, depreciation, rent, and utilities. This approach is straightforward and easier to prepare as it does not require allocating expenses to specific functions or activities. It is commonly used in single-step income statements and is particularly suited for smaller organisations or those with simpler financial reporting requirements.

Functions of Expenses

The "functions of expenses" classification, on the other hand, groups expenses based on the purpose they serve or the activities they support within an organisation. Expenses are allocated to categories such as cost of sales, administrative expenses, and selling and distribution expenses. This method provides a deeper insight into how resources are used within different functional areas of the business. It is typically used in multi-step income statements, offering more detailed information for stakeholders to assess operational efficiency and profitability.

Key Difference

The primary distinction lies in their focus: the "nature of expenses" method looks at what the expense is, while the "functions of expenses" method examines why or how the expense is incurred. The choice between these methods often depends on regulatory requirements, industry practices, and the level of detail needed for decision-making.

Earnings Per Share (EPS) and its Relation to the Income Statement

Earnings Per Share (EPS) is a critical financial metric that represents the portion of a company’s profit allocated to each outstanding share of common stock. EPS is directly related to the income statement, as it derives its value from the net profit or net earnings reported.

EPS Formula:

Relation to the Income Statement:

- Net Profit: The starting point for EPS calculation is the net profit, the final line item on the income statement.

- Preferred Dividends: If a company has preferred stock, the dividends paid on these shares are subtracted from the net profit since they are not available to common shareholders.

- Weighted Average Shares: This denominator incorporates any share issuance or buyback activities during the period.

Example:

Company ABC’s Income Statement shows:

- Net Profit: EUR 500,000

- Preferred Dividends: EUR 50,000

- Weighted Average Shares: 200,000

This indicates that each share earned £2.25 during the period.

EPS helps investors gauge the company’s profitability on a per-share basis, making it a key metric for valuation and decision-making.

Vertical Analysis

Vertical analysis expresses each item on the income statement as a percentage of a base figure, typically net sales (total revenue). This method highlights the relative size of each component, providing insights into cost structure and profitability.

Formula:

Example:

Income Statement for XYZ Ltd:

| Particulars | Amount | Percentage of Net Sales |

|---|---|---|

| (EUR) | ||

| Net Sales | 1000,000 | 100.0% |

| Cost of Goods Sold | 600,000 | 60.0% |

| Gross Profit | 400,000 | 40.0% |

| Operating Expenses | 250,000 | 25.0% |

| Net Profit | 150,000 | 15.0% |

Insights:

- 60% of net sales is consumed by direct costs (COGS).

- 15% of net sales translates into profit, indicating potential areas for cost efficiency.

Horizontal (Trend) Analysis

Horizontal analysis compares financial data over multiple periods to identify trends in revenues, expenses, and profitability. This method uses a base year as a reference to calculate percentage changes for subsequent periods.

Formula:

Example:

Income Statement Data for ABC Ltd (Three Years):

| Particulars | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | % Change (Year 2 vs Year 1) | % Change (Year 3 vs Year 2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (EUR) | (EUR) | (EUR) | |||

| Net Sales | 900,000 | 1000,000 | 1200,000 | 11.1% | 20.0% |

| Cost of Goods Sold | 540,000 | 600,000 | 720,000 | 11.1% | 20.0% |

| Gross Profit | 360,000 | 400,000 | 480,000 | 11.1% | 20.0% |

| Operating Expenses | 240,000 | 250,000 | 270,000 | 4.2% | 8.0% |

| Net Profit | 120,000 | 150,000 | 210,000 | 25.0% | 40.0% |

Insights:

- Net sales and cost of goods sold have grown consistently, maintaining a steady gross margin.

- Net profit has grown at a faster rate than revenues, suggesting improved operational efficiency.

- Operating expenses show slower growth, indicating effective cost management.

By incorporating EPS, vertical analysis, and horizontal analysis with practical examples, stakeholders gain a comprehensive understanding of the income statement. These methods provide insights into profitability, cost management, and financial trends, equipping decision-makers with actionable information.

Conclusion

The income statement is more than a document; it is a narrative of financial performance that captures the essence of an organisation’s operations and strategic decisions. For accounting students, mastering its components, mechanics, and significance is a gateway to understanding broader financial principles and practices. By delving into the intricacies of the income statement, students can equip themselves with the analytical tools needed to assess and improve the financial health of any organisation. The journey from gross profit to net profit is not just a series of calculations but a story of value creation and allocation, central to the world of accounting and business. By appreciating its role, students can transform numbers into insights and data into decisions, becoming adept financial stewards in their professional careers.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

About Us

Legal

Copyright ©2024 Accounting Training. All Rights Reserved

Course Outline

- Concepts and Accounting

- The Three Different Natures of Accounts

- The Accounting Equation

- Accrual Accounting

- Debits and Credits

- The Journal

- Bank Reconciliation

- Adjusting Entries

- Inventory and Cost of Sales

- Depreciation

- Income Statement

- Chart of Accounts

- Accounting Principles

- Financial Accounting

- Financial Statements

- Balance Sheet

- Working Capital and Liquidity

- Cash Flow Statement

- Financial Ratios

- Accounts Receivable and Bad Debts Expense

- Accounts Payable

- Inventory and Cost of Goods Sold

- Payroll Accounting

- Bonds Payable

- Stockholders’ Equity

- Present Value of a Single Amount

- Present Value of an Ordinary Annuity

- Future Value of a Single Amount

- Nonprofit Accounting

- Break-even Point

- Improving Profits

- Evaluating Business Investments

- Manufacturing Overhead

- Nonmanufacturing Overhead

- Activity Based Costing

- Standard Costing